- Home

- Policy Search

- ADDRESSING IMMIGRATION AND REGULATORY BARRIERS TO ATTRACT ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS TO RURAL AND UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES (2025)

ADDRESSING IMMIGRATION AND REGULATORY BARRIERS TO ATTRACT ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS TO RURAL AND UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES (2025)

Issue

The ongoing shortage of allied health professionals in rural British Columbia has become critical, directly impacting the quality and accessibility of healthcare. Professionals such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists play an essential role in recovery, disability prevention, and the overall sustainability of the healthcare system. Care pathways are disrupted without their presence, and access to vital services is significantly affected.

Businesses in these regions are also feeling the impact. Injury management and rehabilitation delays extend work absences, increase costs, and reduce operational efficiency. Inadequate healthcare services compound the issue, making it difficult to attract investment or secure a stable workforce.

The shortage of allied health professionals is more than a healthcare issue; it’s a business risk. Without enough providers to support worker recovery, communities suffer, and business continuity is disrupted. Delays in rehabilitation and return-to-work increase time off, reduce productivity, and increase company costs. Strengthening the local healthcare workforce is key to building healthier communities and more resilient businesses.

Systemic inefficiencies in credentialing, immigration, and registration processes—administered by IRCC and regulatory colleges—have created delays restricting workforce access. While intended to ensure public safety, these processes are often non-adaptive to the evolving needs of rural communities, contributing directly to prolonged service gaps.

Although the Provincial Nominee Program has enabled many businesses to access global talent, its application in rural communities often lacks the mechanisms necessary to ensure retention. Without clear accountability or incentives to remain, candidates frequently relocate to larger centres, leaving the very communities that nominated them without the health professionals they critically need.

Background

Rural British Columbia and underserved areas face a severe and ongoing shortage of allied health professionals, impacting healthcare delivery in hospitals, private clinics, and First Nation health programs. Unlike urban centres, which attract most Canadian-trained allied health professionals, rural areas experience chronic understaffing, leaving patients with limited access to essential rehabilitation and therapy services.

Based on the BC Government's population growth estimates through 2046,[1] the demand for qualified professionals will continue to rise, yet the current supply is not keeping pace.

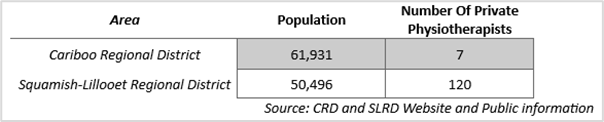

Current workforce data highlight this disparity, using private physiotherapy as an example in the Cariboo Regional District, which has 18 First Nation Communities, and the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District, which has three First Nation Communities. While other allied health professions may face similar challenges, physiotherapy clearly illustrates these discrepancies.

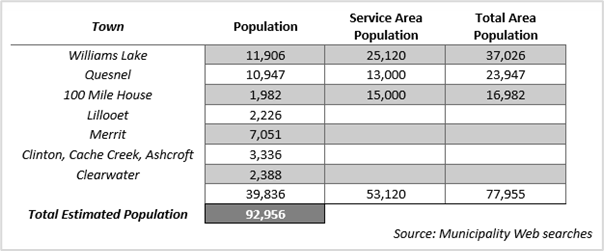

Table 1: Area covered by Interior Health for Allied Health Services, managed from Williams Lake, as well as Quesnel, which is part of the CRD and includes the listed towns

The total estimated population of 92,956 across the region. Despite the size of this population and a service area nearly twice that of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District, access to private allied health services is critically limited. Currently, the region is served by only 7 private physiotherapists, 2 private occupational therapists, and no private dietitians or speech-language pathologists.

Table 2

Communities such as Merritt, Lillooet, Ashcroft, and Clearwater have no local access to private physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, or other allied health services. As a result, residents must travel to larger centres for even the most basic care, which affects individual health outcomes, workforce well-being, and overall community resilience.

When referencing the detailed breakdown of community services,[2] there is a gap. This highlights the urgent need to expand access to allied health services throughout the region.

This lack of available allied health professionals in rural BC has resulted in:

- Extended wait times for patients in need of assessments and treatments.

- Limited access to preventative & rehabilitation services, coupled with delayed and inconsistent treatment.

- Reduced availability of specialized care, requiring patients to travel to urban centers for services.

- Increased workload and provider burnout contribute to higher staff turnover.

- Delays in pediatric care negatively impact developmental outcomes due to a shortage of early intervention services.[3]

Regulatory Barriers Hindering Recruitment

While internationally trained professionals could be critical in addressing workforce shortages, the BC College for Health and Care Professionals imposes excessive credentialing requirements that are bureaucratic, time-consuming, and slow to adapt to evolving challenges. Rather than working to fill shortages, the current credentialing process inadvertently contributes to them. Its rigid, one-size-fits-all approach fails to consider the specific needs of underserved communities, resulting in significant delays and further limiting access to essential healthcare services.

The Northern UNBC program, which was specifically designed to support northern communities, currently retains less than 5% of its graduates in the region annually. No Canadian province presently has a service commitment tied to licensure. British Columbia sees limited enrolment from out-of-province students, most of whom return to their home provinces after graduation. With more than 800 applicants competing for only 120 physiotherapy seats annually, there is a clear opportunity to prioritize admission for residents of BC or other provinces committed to serving in rural and underserved areas.

Implementing a structured service component, informed by community needs, would help ensure that public investment in education results in tangible benefits for regions in need of allied health services.

This approach could also serve as a model for other provinces with similar rural healthcare challenges, offering a strategic solution to improve access, distribution, and long-term retention of allied health professionals. Crucially, improving the availability of healthcare workers in rural regions directly benefits local businesses by enhancing access to timely rehabilitation and preventative care. This helps reduce injury-related downtime, supports faster return-to-work processes, and improves workforce health, contributing to greater business productivity, reduced costs, and economic resilience in rural communities.

Key barriers include:

- The credentialing process for internationally trained professionals is lengthy, taking 1.5-2 years for physiotherapists, 2-3 years for occupational therapists and dietitians, and 1-2 years for speech therapists. These timelines do not account for the additional 0.5-1 year required for immigration processing, further delaying their ability to enter the workforce and address critical shortages.

- In-person exam requirements for certain professions require foreign-trained professionals to travel to Canada before certification. South African applicants, for example, must obtain a visitor visa, which currently takes up to 551 days to process.[4]

- There are no supervised practice options in BC, unlike in Alberta, which allows internationally trained physiotherapists to work under supervision for up to two years while completing credentialing requirements.

- No alternative approaches to credentialing have been explored, and existing programs lack data to demonstrate their effectiveness.

- Credentialing and immigration are treated as separate processes, creating additional barriers and compounding workforce shortages. Without a streamlined, integrated approach, delays will continue to hinder the timely placement of qualified professionals in underserved areas.

Inefficiencies in Immigration Pathways

Despite rural BC’s urgent need for allied health professionals, immigration policies fail to ensure these workers stay in underserved areas. The Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) was designed to attract international workers to fill critical workforce gaps. Still, it lacks enforcement mechanisms, allowing professionals to gain permanent residency without fulfilling their working commitments to rural employers.

As a result, many relocate to urban centres shortly after securing their PR status, leaving rural businesses and health systems in a continuous cycle of recruitment, disruption, and workforce shortages. This instability undermines access to care and the operational continuity of businesses that rely on timely rehabilitation and occupational health services to keep their workers healthy, productive, and on the job.

Moreover, the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) process—the only alternative for many rural employers—is costly, slow, and bureaucratic, creating additional barriers.

- $1,000 per worker application fee, which is non-refundable if denied.

- Long processing times leaving employers with unfilled positions for months.

- Complex advertising requirements, forcing employers to demonstrate failed recruitment efforts before hiring foreign workers.

- LMIA might be denied.

Comparing Canada’s Approach to Other Countries

Canada’s immigration and regulatory inefficiencies make it an unattractive destination for allied health professionals compared to Australia [5], New Zealand, Dubai and Ireland, where streamlined pathways allow for faster credentialing and immigration. For example, Australia offers:

- An Express Pathway that allows eligible professionals to bypass assessment stages and complete licensing remotely.

- A six-month immigration process for many allied health professionals, compared to Canada’s multi-year delays.

- BC will continue to lose potential recruits to countries with faster and more efficient systems without similar reforms.

THE CHAMBER RECOMMENDS

That the Provincial Government:

- Modernizing credentialing processes, Provincial Nominee Program criteria, immigration pathways, and recruitment policies to reflect the unique needs of rural communities is essential to addressing allied health professional shortages. These reforms are critical to attracting and retaining internationally trained professionals, strengthening healthcare capacity, and ensuring continued access to crucial services across rural British Columbia.

- Assessing BC’s regional workforce needs, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all model, helps address provider shortages and reinforces the College’s public protection mandate by promoting equitable access to care across the province. Prioritizing the timely integration of internationally trained professionals and expanding allied health services in rural areas are critical steps toward building healthier, more resilient communities.

- Implementing an Interim Registration pathway in BC would allow internationally educated allied health professionals to begin practicing under supervision while completing licensure requirements. This pathway has already been successfully adopted in provinces such as Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, PEI, and Newfoundland, and would accelerate workforce integration in rural areas.

[1] https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/data/statistics/people-population-community/population/newsletter_08_2024_bc_population_projections.pdf

[3] Temporary residence (visiting, studying, working) > Visitor visa (from outside Canada) > South Africa (as of February 25, 2025) https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/managing-your-health/early-childhood-health/ei_therapy_guidelines.pdf